Discovery of new proteins that maintain DNA ends

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHT

1 June – The teams of Falk Butter and René Ketting at the Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB) published a paper in Nature Communications identifying two new proteins that bind to the ends of chromosomes in the nematode worm C. elegans, a popular model organism for ageing studies.

In eukaryotes, DNA occurs as a long, linear molecule, which is folded and organised into chromosomes. Chromosome ends are particularly susceptible to damage, which can lead to chromosome fusions, breakage and mutations. To prevent this damage, the chromosome ends are protected by repetitive DNA sequences called telomeres. These telomeres are bound by specialised telomere-binding proteins, which help protect the chromosome ends and replenish the telomeres when they become too short. If the telomeres become too short, the chromosomes can be damaged, which can in turn lead to cell death, ageing and disease.

The nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is a versatile model organism commonly used in ageing studies. However, we still do not know all the telomere-binding proteins in C. elegans, making it difficult to study how telomeres are regulated this model. Studying telomere-binding proteins in C. elegans is important because it could give new insights into how telomeres work in different tissues of a whole organism, rather than in individual cells.

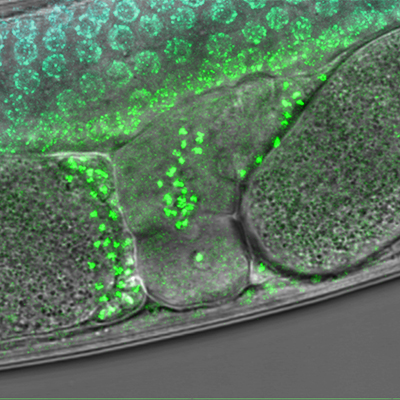

In their new study published in Nature Communications, Sabrina Dietz (from the lab of Falk Butter) and Miguel Vasconcelos Almeida (from the lab of René Ketting) set out to find the unknown telomere-binding proteins in C. elegans. They were also assisted by researchers from the lab of Helle Ulrich (IMB). To do this, they incubated chemically labelled telomeric DNA with proteins extracted from C. elegans, in effect using the telomeric DNA as bait to ‘catch’ any proteins that bind to them. By subsequently isolating the labelled telomeric DNA, they could then ‘pull out’ any proteins that had bound to them. This identified two new telomere-binding proteins, which they named TEBP-1 and TEBP-2 for Telomere Binding Protein 1 and 2. To confirm that these were indeed telomere-binding proteins, the researchers labelled TEBP-1 and 2 with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) marker in living C. elegans. Both the fluorescent TEBP-1 and TEBP-2 proteins were located at the telomeres in live cells, strongly indicating that they are bona fide telomere-binding proteins.

Next, the researchers wanted to find out what functions these new proteins might have in telomere regulation. To do this, they created C. elegans mutants with deletions of the genes encoding the TEBP-1 and 2 proteins. Worms without TEBP-2 had shorter telomeres than normal worms, suggesting that TEBP-2 promotes telomere lengthening, while those without TEBP-1 had longer telomeres, suggesting that this protein counteracts telomere lengthening. Interestingly, worms without TEBP-2 also had a reproductive defect and produced fewer and fewer offspring over many generations until they became completely sterile. The authors speculate that this is likely due to a defect in the proliferation of the cells that give rise to eggs and sperm. As Sabrina says, “Without TEBP-2, the telomeres are not replenished and become shorter in each generation. This leaves the chromosomes susceptible to damage, which could cause problems in cell division and result in cell death and sterility over many generations.” Worms without both TEBP-1 and TEBP-2 had an even stronger effect, with sterility occurring in only one generation.

These results shed more light on how cells protect their chromosomes from damage in this popular model organism. The researchers next plan to further investigate how TEBP-1 and 2 control telomere length and how this is linked to fertility, especially in worms without both TEBP-1 and TEBP-2.

Cheryl Li is a Science Writer at the Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB)

The image above is a cropped, false-colored image taken from the original paper, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Further details

Further information can be found at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-22861-2.

Falk Butter is a Group Leader at IMB. Further information about research in the Butter lab can be found at www.imb.de/butter.

René Ketting is a Scientific Director at IMB. Further information about research in the Ketting Lab can be found at www.imb.de/ketting.

About the Institute of Molecular Biology gGmbH

The Institute of Molecular Biology gGmbH (IMB) is a centre of excellence in the life sciences that was established in 2011 on the campus of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU). Research at IMB focuses on three cutting-edge areas: epigenetics, developmental biology, and genome stability. The institute is a prime example of successful collaboration between a private foundation and government: The Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation has committed 154 million euros to be disbursed from 2009 until 2027 to cover the operating costs of research at IMB. The State of Rhineland-Palatinate has provided approximately 50 million euros for the construction of a state-of-the-art building and is giving a further 52 million in core funding from 2020 until 2027. For more information about IMB, please visit: www.imb.de.

Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation

The Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation is an independent, non-profit organization that is committed to the promotion of the medical, biological, chemical, and pharmaceutical sciences. It was established in 1977 by Hubertus Liebrecht (1931–1991), a member of the shareholder family of the Boehringer Ingelheim company. Through its Perspectives Programme Plus 3 and its Exploration Grants, the Foundation supports independent junior group leaders. It also endows the international Heinrich Wieland Prize, as well as awards for up-and-coming scientists in Germany. In addition, the Foundation funds institutional projects in Germany, such as the Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB), the department of life sciences at the University of Mainz, and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg.

Press contact for further information

Dr Ralf Dahm, Director of Scientific Management, Institute of Molecular Biology gGmbH (IMB), Ackermannweg 4, 55128 Mainz, Germany

Phone: +49 (0) 6131 39 21455, Fax: +49 (0) 6131 39 21421, Email: press(at)imb.de